These initial sections give a brief overview of what

Stirling Engines are capable of, what they are and how they work. The brief

nature of these initial chapters is highlighted in chapter 1.2, which is simply

a list of principles and characteristics of the engine, combined with where to

get more information for each principle.

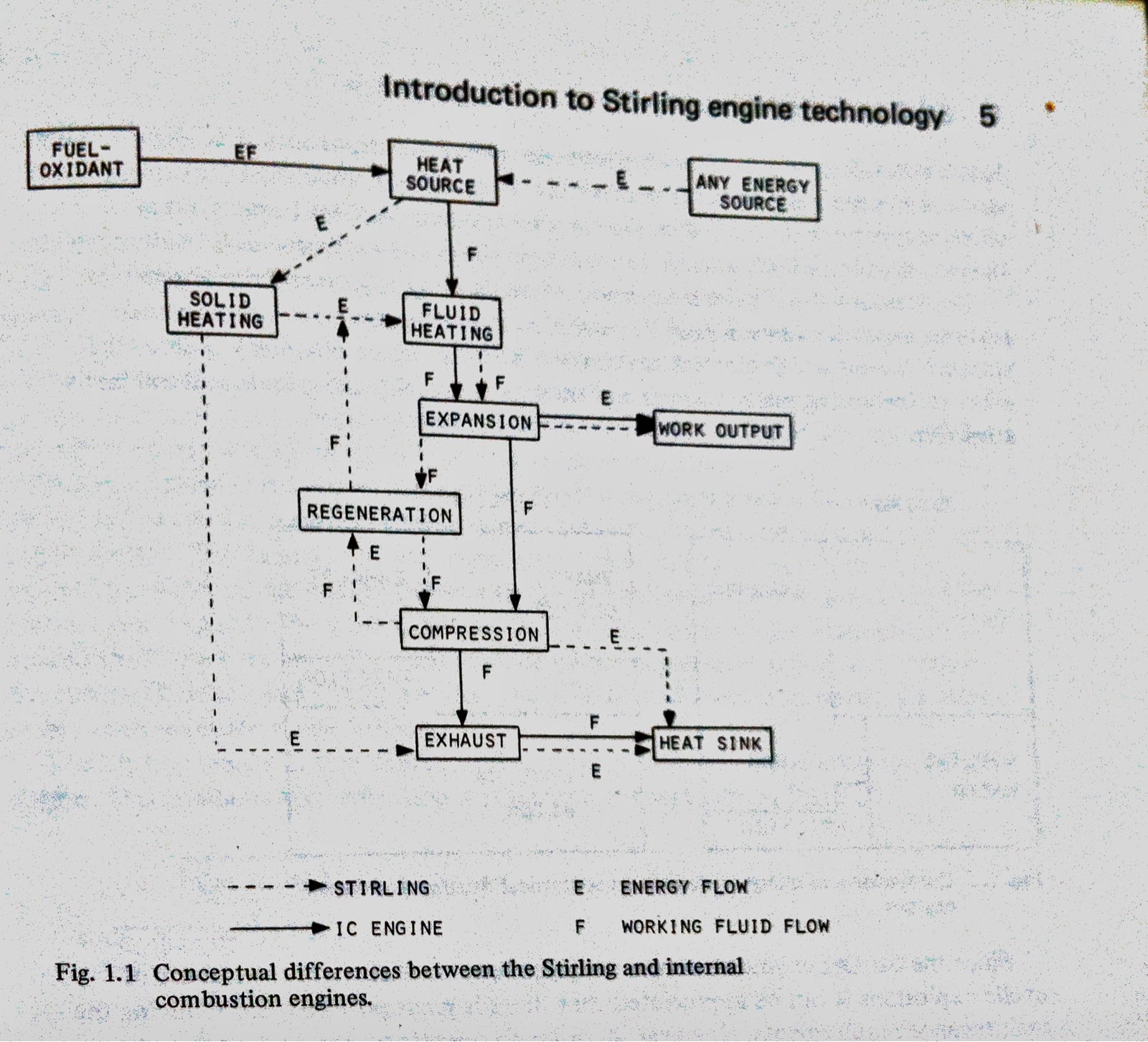

These facts lead into chapter 1.3 – What is a Stirling Engine? This

chapter explains that the Stirling Engine “is a closed regenerative cycle heat

engine which operates at high mean gas pressures, in an oil-free environment,

with no valve gear, with energy transfers through the cylinder walls” (Reader,

4). The chapter continues to show a schematic diagram (to the right) comparing

the differences between the Stirling and Internal Combustion (IC) Engines. From

this diagram I got the impression that the Stirling Engine is a more

sophisticated machine in terms of efficiency and having the ability to utilize

multiple energy sources (off the top of my head an engine that uses the

temperature of water in lakes to power boats or a very sensitive engine that

generates power from the heat of your hand). Furthermore, it appeared that the

IC Engine is straightforward and as a result loses efficiency

and some sophistication. The chapter concludes by introducing the regenerator showing how it improves efficiency.

and some sophistication. The chapter concludes by introducing the regenerator showing how it improves efficiency.

Essentially, these chapters showed that at the Stirling

Engine despite being a very complex machine can be explained using everyday

observations, but full understanding of the Engine requires more knowledge. At

its very basics the Stirling Engine is an air-tight box, in which a pressurized

gas is heated and cooled by an external heat source which increases and

decreases the pressure within the box, moving a piston up and down. Since more

work has to be applied to move the piston upwards than downwards, mechanical energy

can be created. Interestingly, when heat is put into a Stirling Engine

mechanical energy is outputted, but if mechanical energy is put into a Stirling

Engine (by rotating its flywheel) hot and cold heat is outputted (Chapter 1.2).

Although I understand how the former works, this system confuses me as

depending on the direction the flywheel is rotated the location of the hot and

cold heat also reverses. After reading chapters 2.1 (Thermodynamics) and 2.2

(Heat Transfer) I will hopefully better understand how this works.

Essentially, these chapters showed that at the Stirling

Engine despite being a very complex machine can be explained using everyday

observations, but full understanding of the Engine requires more knowledge. At

its very basics the Stirling Engine is an air-tight box, in which a pressurized

gas is heated and cooled by an external heat source which increases and

decreases the pressure within the box, moving a piston up and down. Since more

work has to be applied to move the piston upwards than downwards, mechanical energy

can be created. Interestingly, when heat is put into a Stirling Engine

mechanical energy is outputted, but if mechanical energy is put into a Stirling

Engine (by rotating its flywheel) hot and cold heat is outputted (Chapter 1.2).

Although I understand how the former works, this system confuses me as

depending on the direction the flywheel is rotated the location of the hot and

cold heat also reverses. After reading chapters 2.1 (Thermodynamics) and 2.2

(Heat Transfer) I will hopefully better understand how this works.

The chapter ends introducing the Regenerator which I found

to be a neat, yet very simple idea. Basically, instead of having the heat

sources cool the hot gas all the way down to a cold temperature and losing all

the energy they had the gas flows through a regenerator collecting some of the

heat. Without getting too complex, a regenerator is a group of stainless steel

wires that the gas flows through to pre-cool or pre-heat the gas. This is

because when the gas flows from hot to cold the gas is hotter than the

regenerator. Therefore, the gas gives some of its heat to the regenerator,

cooling the gas while heating the regenerator. When the gas returns, moving

from cold to hot, the gas is colder than the regenerator and therefore is

preheated returning some of the energy it lost during the previous phase. As a

result the regenerator pre-heats and pre-cools the gas, using energy that would

otherwise be lost which makes the engine more efficient. The other parts of the

Stirling Engine are discussed in chapter 1.4, which will be posted shortly.